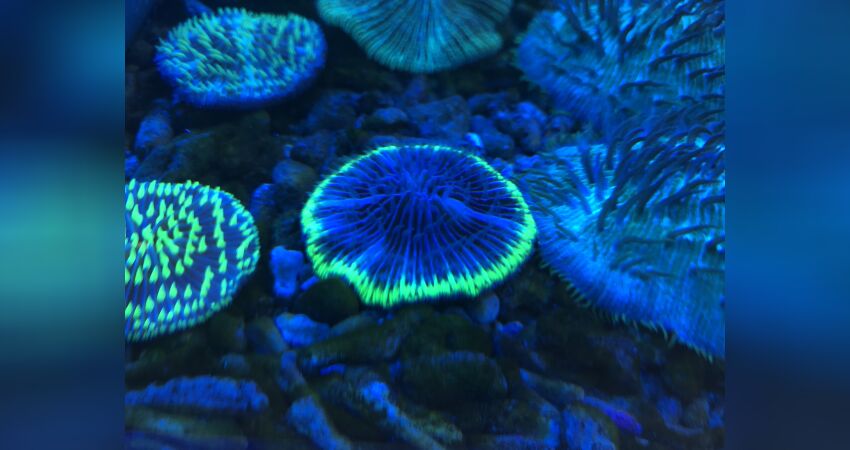

FUNGIA Mushroom Corals

"Fungia" in nature

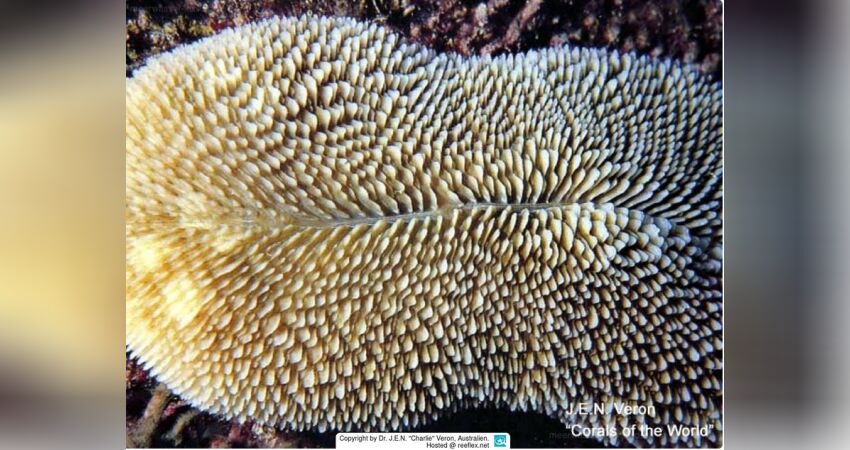

Fungia begin their life in the reef, after the larval phase, firmly grown as individual polyps. Presumably in order not to be so easily overgrown, they first form a small stalk on which the later polyp grows "umbrella-like". This looks deceptively similar to a real mushroom, which is one of the reasons why they got their name. The later polyp then resembles the umbrella of a "real mushroom". This firmly grown stage of life is called acanthocauli. When the polyp is large enough, it breaks off and lives freely mobile from then on. However, not all species are mobile, some continue to grow in a crust-like manner. Depending on environmental conditions, the attached phase can last longer.

This seems to be the case more often, especially in the aquarium. The evenly good conditions, without strong current fluctuations or changes in environmental conditions, seem to be a logical explanation for this. However, the Acanthocauli that remains behind is not dead after the coral falls off. Numerous other polyps can still grow, often even several at a time! The free-moving species seem to have an advantage over the fixed ones (2 Cantharellus, 2 Cycloseris, 3 Lithophyllon, 4 Podabacia). Accordingly, they are found more frequently in the sea. Sometimes real mother polyps develop from the Acanthocauli, which in extreme cases can develop dozens of daughter polyps in one year. If larger polyps die due to environmental influences, sometimes the smallest tissue remnants remain, from which acanthocauli can then grow. It is not uncommon for several mother pieces to develop on a former coral. Hundreds of young corals can easily be grown in this way. In nature, it is possible for mobile species to reach and colonise areas that are less or not accessible to other corals. Why some give up this apparent advantage and continue to grow firmly on the substrate after the acanthocauli stage is unexplained.

The ability to move around opens up some possibilities for corals, but also poses risks. They can easily be flipped over in storms and strong swells. In addition, increased sediment can cause problems in their preferred habitats and they can come into abrupt contact with other corals, which naturally defend themselves. Although free-living, many species are not very mobile according to my observations, e.g. Halomitra, Ctenactisand Herpolitha. All species with several mouths and mostly elongated shape. Polyphyllia talpina, however, was surprisingly mobile in my case. It could expand its tissue similarly well by water absorption as the well-known Heliofungia actiniformis, which is similar to the anemones. I know this species to be very mobile, surpassed only by Heliofungia fralinae, which was placed in Fungia before the reworking. The smaller H. fralinae can, in a healthy state, easily overcome 3-10 times the skeletal diameter of in one day, without any support from water movement. With the use of currents in the water, they can certainly manage far more.

For active movement, the body is firmly inflated with water. The tissue is then taut and really tough. A polyp inflated in this way is not unpleasant to the touch, almost like a rubber ball that is not bulging and only slightly slimy. So not at all soft and vulnerable. It has to be that way, because if they are drifted or turned over in a storm, they must not immediately injure themselves on the sharp-edged substrate. The mobile species rarely inhabit fine loose sand, even in the sea. They colonise areas with a caked substrate and on coral gravel! In many reef areas destroyed by humans today, they thus find suitable habitats. Presumably, the mushroom stony corals could even be among the winners if the coral reefs continue to die off due to environmental destruction. In any case, the habitats suitable for them would increase in the reefs. Whether they can withstand the higher temperatures caused by global warming remains to be seen. In my experience, however, the Indonesian specimens are among the more heat-tolerant stony corals. In some areas you can find aggregations of hundreds of individuals, almost always a community of many different species.

Unfortunately, these are not accessible to a snorkeller like me, such aggregations are usually found in the marginal areas of the reefs, e.g. in depressions where coral gravel collects, mostly below five metres water depth. Only once have I been able to see a smaller aggregation at some distance in the Philippines. In shallow water, almost only single specimens can be seen, but regularly. In the Red Sea, Ctenactis echinata can sometimes be found in shallow water among the large stands of fire corals (Millepora sp.).

Fungia sp. is usually found a little deeper on the reef slope, which can only be reached by snorkellers in very, very favourable wind conditions (swell). In shallow water in the Philippines I could find them regularly, but they were still among the rather rare corals. I particularly remember a beautiful Acanthocauli of a Heliofungia actiniformis. It was all too easy to mistake it for a sea anemone or a Euphyllia stony coral. But I checked it out and it was indeed a mother piece of an H. actiniformis with bright yellow tentacle tips. There were at least 3 daughter polyps on the acanthocauli.

How do you like this article?

Info

Author

Bookmark

Comments

Topics

Similar articles

- Three new Tubastraea corals discovered off Hong Kong

- Information on the Cites obligation for trade and private aquarists

- Octocorallia - Achtstrahlige Korallen

- Über die Pflege von Tubastraea im Aquarium

- How a marine aquarium is created Part 38: When corals become entangled, the fight for settlement space

- NEU von Fauna Marin: SeaTak-Korallenkleber

- Korallenzucht im „Miniriff“

- Ernährungsstrategien bei Korallen

- Das Kleben von Gorgonien und Steinkorallen.

- Coral scions made easy - Markus Gerhardus shows us his breeding methods

Comments To the top

Please register

In order to be able to write something yourself, you must register in advance.